Society: Egyptian calendar

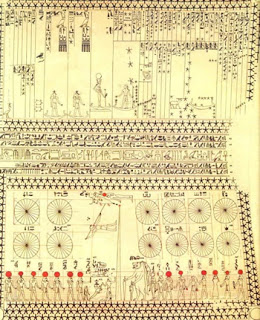

Astronomical ceiling of the Senemut tomb.

Every civilization has developed methods to mark the passage of time and the changing of seasons. Ancient Egypt was no exception, and there are notable features of their calendar system that shed light on broader aspects of their societal and religious life. This calendar is referred to as the Sothic calendar, named after the star Sothis, also known as Sirius.

It's important to clarify that Egyptian years were not measured from a fixed point, such as the birth of Christ or the Roman's Ab urbe condita. Instead, years were counted from the accession of a king to the throne. Thus, the first year of a king's reign marked year one, and this count would reset with the accession of a successor.

The impetus for establishing a calendar, or recognizing the need for one, typically stems from the necessity to measure and manage significant seasonal events or occurrences. In Egypt, no event was more critical than the annual flooding of the Nile River, upon which the entire population's livelihood depended. The flood's magnitude could herald years of plenty or times of famine.

Consequently, predicting the timing of the next inundation was vital. Through observation over several years, Egyptians discerned that the Nile flooded approximately every 365 days. This realization likely spurred the initial efforts to track time and led to the creation of a calendar. With knowledge of when the next flood would occur, they could better prepare, organizing their months to align with activities suited to each season.

This theory was first proposed by O. Neugebauer and has been supported by numerous scholars, bolstered by fresh evidence from the collaborative work of professors Belmonte and Krauss (Belmonte 2009 & 2012). They meticulously analyzed the regnal years listed on the Palermo Stone and observed that, within Dynasty I, two kings reigned concurrently within a single year, dividing the months of that year between them. The first king is recorded as having reigned for 6 months and 7 days of that year, while the second did so for 4 months and 3 days. This concurrent reign is substantiated by the fact that only one flood is documented for both kings' respective periods within that year. Summing up these periods yields only 10 months and 10 days, which is too brief a duration to account for both a lunar and a solar year. Consequently, the most plausible explanation is that the time span between two river floods was being measured.

The calendar utilized in Kemet is historically recognized as the first solar calendar. It was structured into twelve months, each comprising 30 days, further organized into weeks spanning ten days. Concluding the final day of the year's last month, an additional five days were appended—totaling 365 days—dedicated to five deities. Presently, these are referred to as epagomenal days, a term coined by the Greeks.

The rationale behind structuring the year into 365-day periods was influenced not solely by Ra (the sun) but also by Hapi (the Nile River), which annually inundated and irrigated the surrounding lands consistently around the same time frame. The Egyptians were cognizant of an annual discrepancy of six hours, a fact acknowledged since Dynasty III when Imhotep instituted the inaugural calendar reform. Moreover, adhering to 365-day years meant that every four years accrued a one-day lag, culminating in a full solar cycle realignment only after 1460 years.

Accordingly, the year was segmented into three seasons: 'Ajet' or the inundation season occurring from late summer to early autumn; 'Peret' or the growing season spanning winter to early spring; and 'Shemu' or the harvest season from late spring to early summer. Each season lasted four months, subdivided into 12 weeks, with each month containing three weeks. These weeks differed from our contemporary understanding, consisting of ten days—a system established since the Old Kingdom's inception and utilized to dictate the work rhythm for the denizens of the fertile black land.

The months were not named as ours are today; instead, they were sequentially numbered within each season. However, starting from the Middle Kingdom period, each month was given a distinct name. For a practical illustration, consider that any given day might be referred to as the 5th day of the second month of Ajet, in the 6th regnal year of King X. The calendar year, independent of the regnal year count, commenced with the summer solstice and coincided with the onset of the annual floods.

Name of the months from the New Kingdom and later:

NÚMERO MES | ESTACIÓN | NOMBRE ORIGINAL | NOMBRE GRIEGO | FECHA ACTUAL |

1 | Primero de Ajet | Yejuti | Thot | 29 de agosto - 27 septiembre |

2 | Segundo de Ajet | Pa-en-Ipat | Paofi | 28 de septiembre - 27 octubre |

3 | Tercero de Ajet | Jut jer | Athyr | 28 de octubre - 27 noviembre |

4 | Cuarto de Ajet | Ka jer ka | Shiak | 28 de noviembre - 26 diciembre |

5 | Primero de Peret | Ta-Aabet | Tybi | 27 de diciembre - 25 enero |

6 | Segundo de Peret | Pa-en-Mejer | Meshir | 26 de enero - 24 febrero |

7 | Tercero de Peret | Pa-en-imenjetep | Famenat | 25 de febrero - 26 marzo |

8 | Cuarto de Peret | Pa-en-Renenutet | Farmuti | 27 de marzo - 25 abril |

9 | Primero de Semu | Pa-en-jensu | Pajon | 26 de abril - 25 mayo |

10 | Segundo de Semu | Pa-en-Enet | Payni | 26 de mayo - 24 junio |

11 | Tercero de Semu | Apep | Epifi | 25 de junio - 24 julio |

12 | Cuarto de Semu | Mesut-Ra | Mesore | 25 de julio - 23 agosto |

An essential piece of information for verifying the knowledge possessed in the Nile region regarding timekeeping and astronomy is found on the ceiling of Senemut's tomb at Deir el-Bahari, where figures and specific details about lunar cycles, constellations, and time segments are depicted. This astronomical ceiling has been the subject of much debate; it remains a topic of discussion in several areas where there is no clear consensus on what is depicted and how it is presented. Notably, it illustrates a division into 24 units (or hours), 12 of which are likely nocturnal.

Another view of the astronomical ceiling of the tomb of Senenmut.

We have observed the necessity for time measurement, its potential emergence, and the organization of seasons, weeks, and regnal years, along with brief insights into Senemut's tomb's astronomical ceiling. However, what remains uncertain through scientific means is whether these calendars, computations, and theories significantly impacted the daily lives of ordinary Nile Valley inhabitants or if they were merely administrative and religious instruments with minimal influence on regular workers, aside from structuring their workdays into 10-day weeks and dictating local and national festivals.

As is often the case when delving into ancient Egyptian culture, our findings predominantly reflect an administrative and religious elite. Consequently, it is exceedingly challenging to deduce their effect on or perception by the general populace.

Bibliography:

Castro Martín, Belén - A historical review of the egyptian calendars: The development of time measurement in ancient egypt from Nabta Playa to the Ptolemies

Llagostera Cuenca, Esteban - La medición del tiempo en la Antigüedad: el calendario egipcio y sus "herederos"

Neugebauer, O - The Origin of the Egyptian Calendar

Vivas, Francisco - Algunas observaciones en torno al calendario del monumento de Senenmut y el posible objeto astronómico representado en su techo.

Wilson, Ja, Torner Fm - La cultura egipcia (1953)

Comments

Post a Comment