Contradictory myths. Coherence.

One aspect that can be confusing when discussing Kemet is the apparent contradictions within certain myths or narratives. There are multiple creation stories, as well as a variety of gods who have different forms yet perform identical functions, assimilations of gods, and other elements that may seem overly complex to those unfamiliar with the culture.

It's important to recognize that Kemet's culture spans a vast period of over 2,500 years. During this time, beliefs and cultural practices were subject to change and transformation.

Therefore, it's not unexpected for certain deities to fade from prominence or for local gods to gain importance and become national figures depending on the circumstances. Regarding contradictory myths—the primary focus of this discussion—it should be noted that these contradictions were not only acknowledged throughout history but were also harmoniously accepted. As paradoxical as they may seem, they were considered consistent within the broader context.

To illustrate this point, let's examine several examples. When it comes to the creation of the world, we observe that different regions attribute creation to different deities. However, there is a widely accepted creation myth in the general consciousness. Aside from this overarching narrative where several elemental gods play roles in the north, in Taui, Ptah is revered as a demiurge. Further south, one might encounter Khnum or Thoth performing similar functions.

Does this mean that in someone's mind, some were right and others wrong? No. This is not like in a religion where those who worship other gods are wrong and they are the only ones who are right. The gods are consistent throughout Kemet, and although it is logical for the local god to have greater presence and prominence in the myths, the foundation is the same. Therefore, there could be different versions of the myth because, in the end, they all convey the same principles. It could be understood that two gods might have created the world in different ways.

This way of understanding the gods is called henotheism. Unlike monotheism, where there is only one god, or polytheism, where there are many gods, henotheism allows for the same god to exist as the only one without excluding a plurality of gods. Henotheism, as cited by PIULATS (2006), is “defined by the German romantic philosopher Schelling. He was the first to designate by the term henotheism a religious model beyond polytheism and monotheism that was capable of expressing worship simultaneously to a single god without excluding a plurality of gods.”

What may sound incongruous to our minds, accustomed to religious dichotomies, was generally accepted in Kemet culture. The gods and other elements do not contradict each other but complement each other. It should also be considered that people did not have the possibility of traveling from one city to another and coming into contact with other myths. Essentially, an ordinary person was confronted with local and national myths, which may or may not match, and he was rarely immersed in other stories.

The population was changing over time, and myths were evolving or disappearing. This aspect is often overlooked when discussing the stories of Kemet and their societal impact. It's common to generalize and apply it to the entire narrative, disregarding the specific context of each era and locale. An inhabitant of Taui (Memphis), when it was the capital, revered Ptah as the chief deity, but also worshipped Ra when he was the national god of the country. Similarly, when Amun rose to prominence as the state god, he superseded others but did not completely erase them.

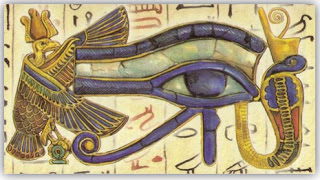

For a resident during Neterkhet Djoser's time in Taui, Ptah was a principal god, as were Ra and Heru (Horus). There was no contradiction in this because each deity could assume different or even identical roles within certain contexts. However, that individual passed away, society evolved, and when Amun became the primary national deity, that same person was no longer there to witness this shift. Consequently, those living during Amun's ascendancy were accustomed to his greater influence compared to Ptah, for example.

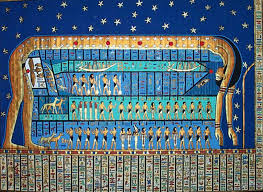

One important aspect to consider is the duality inherent in Egyptian thought. This concept was prevalent among all social strata, from the general populace to the elites, including priests and nobles. They perceived the world as filled with opposing forces that were essential for existence. Just as the sun rises each morning and sets each night, good is balanced by evil, the fertile black land (Kemet) contrasts with the barren red land (desert), and Horus is complemented by Seth.

This worldview is reflected in numerous myths and cosmological explanations, where the absence of one element would render another meaningless or outright non-existent.

In essence, while there may be various versions of a myth or different narratives featuring alternate protagonists, these were not regarded as contradictions. Instead, they represented a logical duality, illustrating different facets of a singular concept.

OTHER ENTRIES

Comments

Post a Comment