Sources and interpretations of the culture of ancient Egypt

Egyptian culture and mythology stand as one of the most intricate and fascinating systems of belief. Unlike Greek, Norse, or Inca mythologies, which present a wealth of narratives unified by a clear internal logic and supported by extensive oral and written traditions bringing them closer to our understanding, Egyptian mythology—referred to as Kemet in ancient times—does not follow this pattern. In the following discussion, we will delve into the reasons behind this and attempt to unravel the complex mechanisms that sustained the religious coherence of a civilization that thrived for over two millennia.

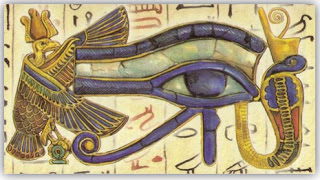

As we delve into Egyptian mythology, we encounter an array of deities that manifest in diverse forms. A single god may be depicted in vastly different manners, such as an animal or an animal-headed human, for instance. This deity may merge with others, spawning new divine entities and iconographies, and may assume varied roles. Similarly, creation myths vary based on their city of origin and are championed by different gods.

Navigating such a landscape makes it challenging to formulate a definitive and singular notion of a god or myth within Egyptian mythology. Acknowledging this multiplicity is essential. The quest for a solitary, authoritative text or a monolithic definition of any concept is futile, as it simply does not exist. Unlike other mythologies where one might find a comprehensive entry or reference for a deity encompassing their entire saga and attributes, such uniformity is unattainable in the realm of Kemet without acknowledging its nuances and the multitude of mythological interpretations or versions of the deity. Consequently, one cannot conclusively state: "Ra is the god of... and symbolizes..."

Why is this the case? There are several reasons. Nonetheless, there exists a logical consistency within the seeming disarray of Egyptian myths, which will become evident at the conclusion of this discussion after elucidating the reasons behind this perceived chaos.

Firstly, the concept of time is crucial. We discuss a society that has thrived for over two millennia under an advanced civilization. Our current inability to fully grasp the significance of this temporal aspect stems from our limited modern benchmarks. To comprehend, we must consider all events from the Industrial Revolution to present-day Europe, recognizing that despite numerous transformations, evolutions, and two world wars, it represents merely a fraction of the duration of Egyptian civilization.

Similarly, other societies geographically and culturally closer to us exhibit shorter lifespans. The Roman Empire, including its republic phase, lasted less than a third of the Egyptian civilization's duration. The Greeks fell short of the Romans in longevity, and civilizations like the Vikings endured barely over 300 years. These civilizations are mere footnotes in the extensive timeline of Egyptian society, yet they seem to have persisted longer than they actually did.

This perspective necessitates acknowledging that the deities and myths that emerged at the dawn of Egyptian society were not identical to those two thousand years later. Remarkably, they underwent less transformation over such an extended period than the aforementioned societies. In 'The Last Stage,' I endeavor to elucidate each deity's significance and the alterations they experienced throughout the various phases of Egyptian society.

Secondly, there is a documentary aspect. Our knowledge of ancient civilizations comes primarily from documents and written texts passed down through generations. In Kemet, writing was present from the onset of its civilization, leading one to assume we should have knowledge comparable to that of Roman or Greek cultures. However, this is not the case. The predominant use of writing for sacred or civil documentation means that our current records are predominantly of this nature. The literacy rate among ordinary people was low, and durable writing materials were limited to papyrus, stone, or ostraca.

Consequently, our understanding of the Kemet civilization is shaped by religious and administrative texts. With scant sources from common individuals, Egyptology attempts to extrapolate habits, beliefs, and culture from the available information to the general populace. Thus, our perception of myths and gods is influenced by temple narratives and sacred texts, which may not align with the commoner's views.

An additional complication arises from the numerous later accounts about Egyptian civilization, particularly by Greek authors like Herodotus. Their descriptions of Kemet's gods and myths—viewed through a Greek lens—often resulted in confused, modified, or altered narratives. This makes it challenging to discern whether information comes from original sources or was added centuries later. The continued worship of some deities under different names and roles further obscures our understanding of the original myths when compared to ancient sources.

Thirdly, the phenomenon known as cultural contamination must be considered. As previously mentioned, throughout history, the Greeks, Romans, Persians, and Arabs have exerted influence and maintained a presence in the Nile region. This interaction has led to the blending of various cultural elements, with some being assimilated into the new culture or altered to align with what the new society is more inclined to accept or comprehend. The Greeks, for instance, renamed all deities and cities, mapping them onto their own pantheon to facilitate understanding, which unfortunately resulted in oversimplification.

Contrary to popular belief, Greek and Egyptian deities are distinctly different. Imposing such assimilation, at times excessively as in the case of Serapis, only serves to obscure or supplant the original concept. Egyptologists have consistently grappled with this issue of cultural contamination. While not all original meanings have been preserved, a significant portion has been salvaged thanks to extant primary sources—scarce as they may be—and by clearly distinguishing between what is derived from later influences and what is authentically original.

In conclusion, the diverse sources available to Egyptology enable a comprehensive study of Egyptian society from every conceivable perspective. Written records have been discussed previously; however, equally if not more critical for discerning behavioral patterns, migratory trends, or the evolution of language and customs are the fields of physical anthropology and paleopathology. These disciplines facilitate cultural analysis through human remains, DNA, artifacts, and comparative studies with findings from different periods within the same region.

To accurately reconstruct the myth and original functions of the gods, we must rely on primary written sources. Although these sources primarily reflect the perspectives of religion and administration, they are invaluable. Similarly, when delving into Egyptian mythology, it's crucial to keep an open mind and consider the nuances previously discussed. It's essential to acknowledge that a single definition for a concept may not exist and that a god can embody various, sometimes contradictory, forms and functions while maintaining a consistent identity.

OTHER INTRODUCTION ENTRIES

Comments

Post a Comment